Der Erlkönig (The Elf King) is now the second piece I have discussed by composer Franz Schubert. It’s, therefore, a little odd that, for most of my formal education, I was not a fan of his work. It wasn’t that I disliked Schubert’s music. In fact, I found some of it to be quite beautiful- too beautiful. I just could not see how his pretty ditties for piano and voice could ever compare the the grandeur of Mozart’s operas, the drama of Beethoven’s symphonies, the technical achievement of Bach’s fugues.

To put it frankly, I was wrong. Very wrong. In fact, those of you who do not like Schubert, unless he, with malice of forethought, murdered your dog, are also wrong.

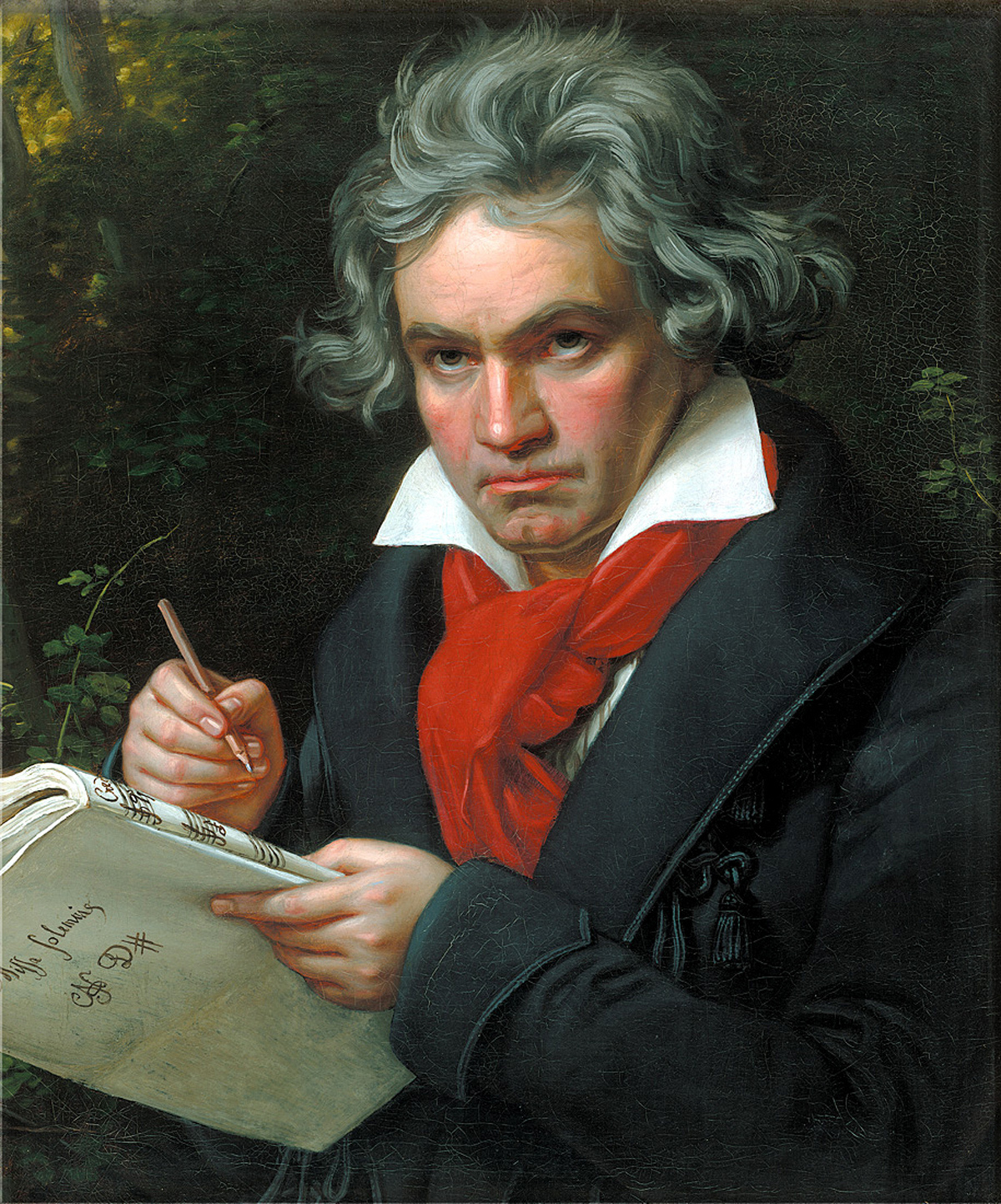

Schubert was an early Romantic composer of art songs. Beethoven, as we know from previous entries, was in very large part responsible for the shift from the Classical to the Romantic period. However, though Beethoven may have fathered German Romantic composition, it was Schubert who perfected it. The Sturm und Drang (storm and drive, aka emotional tides and upheaval) of Beethoven’s symphonies were limited by adherence to compositional forms. Such is not the case for Schubert, partially due to his choice to explore a “lower” form of music, the art song, and partially because he believed the emotion of the piece should dictate its form, not vice-verse.

While Gratchen am Spinnrade is a favorite of mine, it is not Schubert’s crowning achievement. He is forever held in high regard in the annals of music history for two compositions: the sprawling, morose, hour-long Winterreise and the quick snack of adrenaline that is Der Erlkönig. Today we discuss the latter.

Before we watch the video, let’s look at the lyrics. Since this song is all plot, we need to understand what is going on.

Who rides, so late, through night and wind?

It is the father with his child.

He has the boy well in his arm

He holds him safely, he keeps him warm.

“My son, why do you hide your face in fear?”

“Father, do you not see the Elfking?

The Elfking with crown and cape?”

“My son, it’s a streak of fog.”

“You dear child, come, go with me!

Beautiful games I play with you;

many a colourful flower is on the beach,

My mother has many a golden robe.”

“My father, my father, and heareth you not,

What the Elfking quietly promises me?”

“Be calm, stay calm, my child;

Through scrawny leaves the wind is sighing.”

“Do you, fine boy, want to go with me?

My daughters shall wait on you finely;

My daughters lead the nightly dance,

And rock and dance and sing to bring you in.

“My father, my father, and don’t you see there

The Elfking’s daughters in the gloomy place?”

“My son, my son, I see it clearly:

There shimmer the old willows so grey.”

“I love you, your beautiful form entices me;

And if you’re not willing, then I will use force.”

“My father, my father, he’s touching me now!

The Elfking has done me harm!”

It horrifies the father; he swiftly rides on,

He holds the moaning child in his arms,

Reaches the farm with great difficulty;

In his arms, the child was dead.

What on Earth is that about?! There’s a kid and his dad and an elf king, and then there was touching… possibly BAD touching… And then the kid DIES?! That’s some heavy stuff! Like Gretchen am Spinnrade, this piece is also an adaptation of the poetry of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. His poetry was very popular among composers during the Romantic period. It had MEAT in it- love, death, drama, despair, anger. How can we possibly shove all of this plot and emotion into a four minute song?

The piece starts with the piano, frantically pounding out triplets, mimicking the sound of a horse’s hoof beats. This motif will continue throughout the whole piece, adding tension and coloring the scene. But while the piano is quite impressive in this piece, it is the vocalist that takes center stage.

This rendition is performed by the incomparable Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. The composition is quite a tall order, requiring the vocalist to perform as narrator, child, father, and elf king, all very different in tone and character.

Dieskau begins the piece as narrator, setting the scene. As narrator, he has the opportunity to discuss the action in the third person, as an impartial observer. We see him sing with gravity and purpose but very little emotional investment. He is just the narrator, telling us of the action.

Then, at 0:55, his demeanor changes. The change is slight, and you might not catch it at first. His voice lowers, his eyebrows lower. He is the father now, singing to his scared child. At 1:05, the child answers, his eyes unfocused, his voice and brow high, innocent, confused, curious, and afraid. “Father, do you not see the Elf King?” The father comforts the child at 1:20. “My son, it is a streak of fog.”

At 1:28, a sweet melody lilts into the mix. This is our Elf King. He is charming and saccharine, beckoning to the boy. His is a siren song, a happy and soft ditty in stark contrast to the fear and tension of the scene. The effect is eerie, especially with Dieskau’s unblinking smile.

So the story continues, vaulting us from character to character. Look back at the lyrics and try to pick out each individual part. The Elf King is characterized by a fey tone, sung in a high, enticing register, his face merry and disconcerting. The father is characterized by his low, soothing voice and brow furrowed with concern. The child launches further and further into confusion and fear, eyes wild, practically shrieking by the end. Listen for those changes. Look for those changes.

At 3:00, the Elf King takes on a more sinister mien. His song isn’t as pretty as it was before, and there is sense that this creature is a predator ready to pounce. And pounce he does, touching the boy, hurting him.

The boy cries at 3:09, “My father, my father! He’s touching me now! The Elf King has hurt me!”

The piano and the narrator take on a fever pitch, rushing home as quickly as possible. But with a swift climb up the piano keys, the boy and his father arrive home, the horses slowing to a stop, just in time for the narrator to tell us what we already know to be true: “In his arms, the child was dead.”